Self-portraits are more than reflections; they are windows into the artist's soul, revealing layers of identity, emotion, and societal influence. They allow artists to explore their inner worlds and express their perceptions of self, bridging the internal and external. This genre of art provides profound insight into the human condition, capturing both the physical appearance and the psychological and emotional states of the artist. Creating a self-portrait can be deeply introspective, where artists confront their own image and the multiplicity of identities they embody. This dynamic interplay of self-perception and societal influence makes self-portraiture a compelling and enduring form of artistic expression.

In Amoako Boafo's lithograph Self-portrait (Yellow) from 2020, this genre blends personal narrative with broader themes of race and diaspora. Boafo's work vividly explores identity and the complexities of being a Black artist in a predominantly Eurocentric art world. The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan introduced the concept of the "mirror stage," where a child first identifies with their reflection, shaping their sense of self. This idea resonates in self-portraiture, where the artist's depiction becomes a dialogue between internal self-perception and external representation. In Self-portrait (Yellow), Boafo uses a striking yellow backdrop to highlight the textured dark colors of his face, suggesting a complex interplay between self-perception and external perception. This is particularly poignant given Boafo's experiences navigating his Ghanaian heritage and his position within the European art scene, making his self-portraits powerful commentaries on race, identity, and the African diaspora.

Egon Schiele. Self-Portrait with Physalis, 1912. Oil and opaque color on wood, 12 11/16 in × 15 11/16 in (32.2 × 39.8 cm). Courtesy of the Leopold Museum-Privatstiftung, Vienna, Austria.

Egon Schiele, a prominent figure in early 20th-century Vienna, was known for his unflinching self-examination. Schiele's 1912 Self-Portrait with Physalis is a study in psychological intensity, where his gaunt, skeletal form reveals his inner turmoil. Schiele once said, "I do not deny that I have made drawings and watercolors of an erotic nature. But they are always works of art. Are not we ourselves nature, and all our thoughts and feelings as well?" (Kallir, Jane. Egon Schiele: The Complete Works, p. 145). His work delves into the raw depths of human emotion, a trait echoed in Boafo's layered portrayal of his visage. The angular lines and almost grotesque realism in Schiele's work confront the viewer with an unfiltered look at the artist's psyche, a technique Boafo employs, though his approach focuses on texture and color to convey depth and emotion.

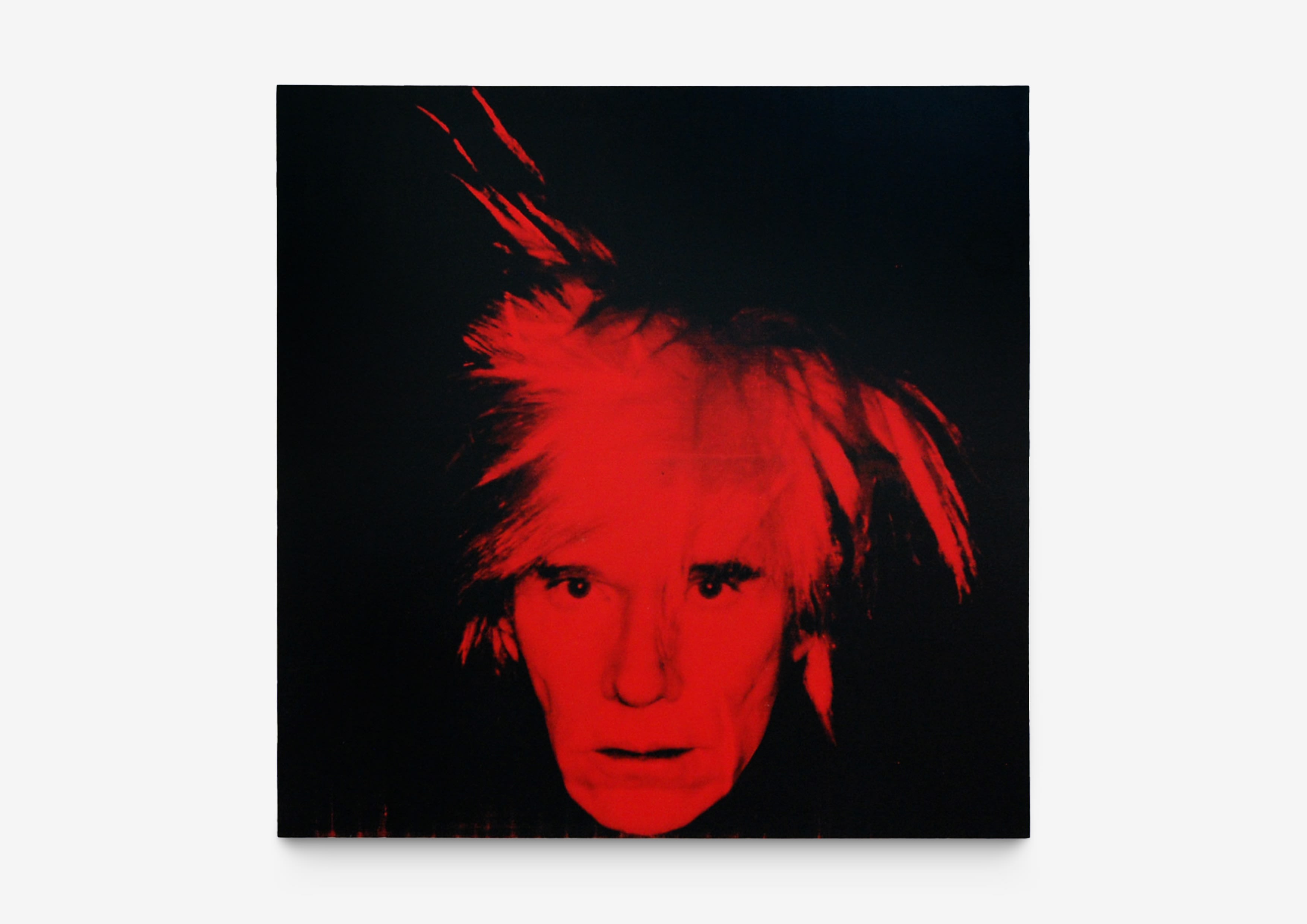

In post-war America, Andy Warhol's self-portraits reflect a different kind of exploration. Warhol's 1986 Self-Portrait (Fright Wig) examines the constructed nature of identity in a media-saturated world. Warhol's exaggerated, often artificial self-representations comment on the surface-level perceptions perpetuated by media. "If everybody's not a beauty, then nobody is," Warhol famously remarked (The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, p. 68), highlighting his fascination with the superficial and the performative aspects of identity. Warhol's use of bold, contrasting colors and repetitive imagery in his self-portraits elaborates on consumer culture and the concept of celebrity. This constructed identity resonates with Boafo's bold use of yellow and the textural depth in his lithographic self-portrait, where he navigates his public persona as an African artist in a predominantly Caucasian environment.

Andy Warhol. Self-Portrait (Fright Wig), 1987. Acrylic paint and screenprint on canvas, 80 x 80 in (203.2 × 203.2 cm). Courtesy of Tate London, UK.

Boafo's Self-portrait (Yellow) shares visual and conceptual threads with both Schiele and Warhol. The expressive lines and emotional depth of Schiele find a modern counterpart in Boafo's textured face, while Warhol's exploration of identity and the appeal of mass media through color and contrast resonates in Boafo's bold use of yellow. Each artist uses self-portraiture to grapple with their identity within their cultural and historical context. Boafo's experience as a Ghanaian artist in predominantly Caucasian Vienna adds another layer to this dialogue. His self-portraits navigate the intersection of African vernacular depictions and Western artistic traditions. "My work is driven by the desire to have myself, my family, and my friends represented in ways that are positive and beautiful," Boafo explains (Juxtapoz Magazine, March 2020). This drive underscores the importance of self-representation in his art, not just as personal exploration but as broader commentary on identity and representation.

For Boafo and many artists of the African diaspora, self-portraiture is a powerful tool for reclaiming and asserting identity. It negotiates between the personal and the collective, the historical and the contemporary. Boafo's portraits stand at the crossroads of his Ghanaian heritage and his experiences in the Western art world, creating a nuanced narrative reflecting both his roots and his global journey. This is vividly illustrated in his lithographic self-portrait, where the texture of the face, composed of dark, swirling lines, contrasts sharply with the bright, flat yellow background. This contrast highlights his African features and serves as a metaphor for his experiences in Vienna.

Amoako Boafo. Self Portrait (Yellow), 2020. Lithograph on paper, 28 x 24 1/8 in (71 x 61 cm). Courtesy of Zeit Contemporary Art, New York.

The African diaspora's experience, marked by constant negotiation of identity, informs Boafo's self-portraits. He navigates the vernacular depictions of the self in African art, where self-representation often serves communal or ritualistic purposes, with the individualistic and introspective tradition of Western self-portraiture. In an interview, Boafo expressed, "The way I paint the Black skin with finger painting is very different from how it has been painted historically. This is me trying to put myself and people like me in the spaces where we were not recognized or appreciated" (Contemporary And, 2020). This sentiment is crucial for understanding the role of self-portraiture in his oeuvre. It is not merely about self-exploration but also about representation and reclamation of identity within a broader historical and cultural narrative.

Boafo's work continues to push the boundaries of self-representation, making a significant contribution to the discourse on art, identity, and the African diaspora. His self-portraits are not just personal explorations but powerful statements on identity and representation. They stand as a testament to the evolving nature of self-portraiture, drawing from the legacy of artists like Schiele and Warhol while carving out a unique space in contemporary art.

In Boafo's hands, the self-portrait becomes more than a depiction; it is a vibrant, textured narrative that speaks to the complexities of identity in a globalized world. Through his self-portraits, Boafo engages in a dialogue transcending temporal and cultural boundaries, creating a nuanced and powerful narrative of identity and representation. This ongoing exploration and assertion of identity through art is a testament to the enduring power and relevance of self-portraiture today.