Stemming from a rejection of traditional materials as a result of their association with whiteness, Adebunmi Gbadebo uses hair from members of the African diaspora in her work, which encompasses sculptures, prints, paper, and paintings. Gbadebo views hair as intrinsically connected to history and culture in that it contains DNA, and is thus redolent of her own ancestry and lineage as well as other genealogies of the diaspora. Gbadebo is thus able to center Black people and histories as central aspects of the narrative through the medium in and of itself. The artist also used indigo dye and rice paper in addition to human hair in the series A Dilemma of Inheritance, a series inspired by her ancestors’ enslavement on two plantations in South Carolina. As some of this land now comprises a luxury golf course, Gbadebo has brought to light a narrative erased by history. All of her works can be viewed as conceptual archives steeped in history and memory. Gbadebo received her BFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York. Her work is currently included in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the Minnesota Museum of American Art. She has also been included in solo and group exhibitions worldwide.

In a few words, how would you describe abstraction?

Abstraction is an expansive language. It is an autonomous zone for identity.

What draws you to abstraction? What do you consider to be its relevance in today’s World?

My practice is seeking life and logic outside of representational and figurative means. Education systems at every level and discipline are steeped in the vantage of a White perspective. My response is to choose a material and process literally rooted in Blackness. I landed on Black hair as a material as it’s evocative of our histories and bodies, so it gives me space to look at the scope of humanity through texture. It’s a material so loaded and full of information, abstraction makes it possible to cover more ground. It ejects the work from a linear timeline. The expectation for Black artists to be included or join representational traditions is a burden because it often flattens and denies our experience–making us invisible even when present. Leaning into invisibility, loss, and survival, abstraction is freedom.

Based on the evolution of abstraction, where would you say your work fits in the arc?

To fully understand the arc in which my work fits in, there has to be more time after me. What I do know about this current moment is that there is a proliferation of Black representation–Black joy, Black violence, Black thought, Black trauma, etc.–marketed on our social media timelines, magazine covers, TV screens, and daily life. I think I belong to the groups of artists who are moving to abstraction to dissolve, process, or expand these representations and express something authentic. I think I am working in tandem with those artists who are rethinking, questioning, and redefining what an art material is or how to make an image. Those artists who feel the limitation in figuration and representation and who have moved to abstraction because of its expansiveness. So in that sense, I guess I evolved from those artists of the past who were concerned with the same questions from the Dadaist who were rejecting traditional modes of art making to the Black abstractists of the '50s and '60s who were questioning and pushing abstract painting, material, the political climate, and identity. But what comes after me that will continue this arc, it’s too soon to call. I just hope my work will be a part of its impact.

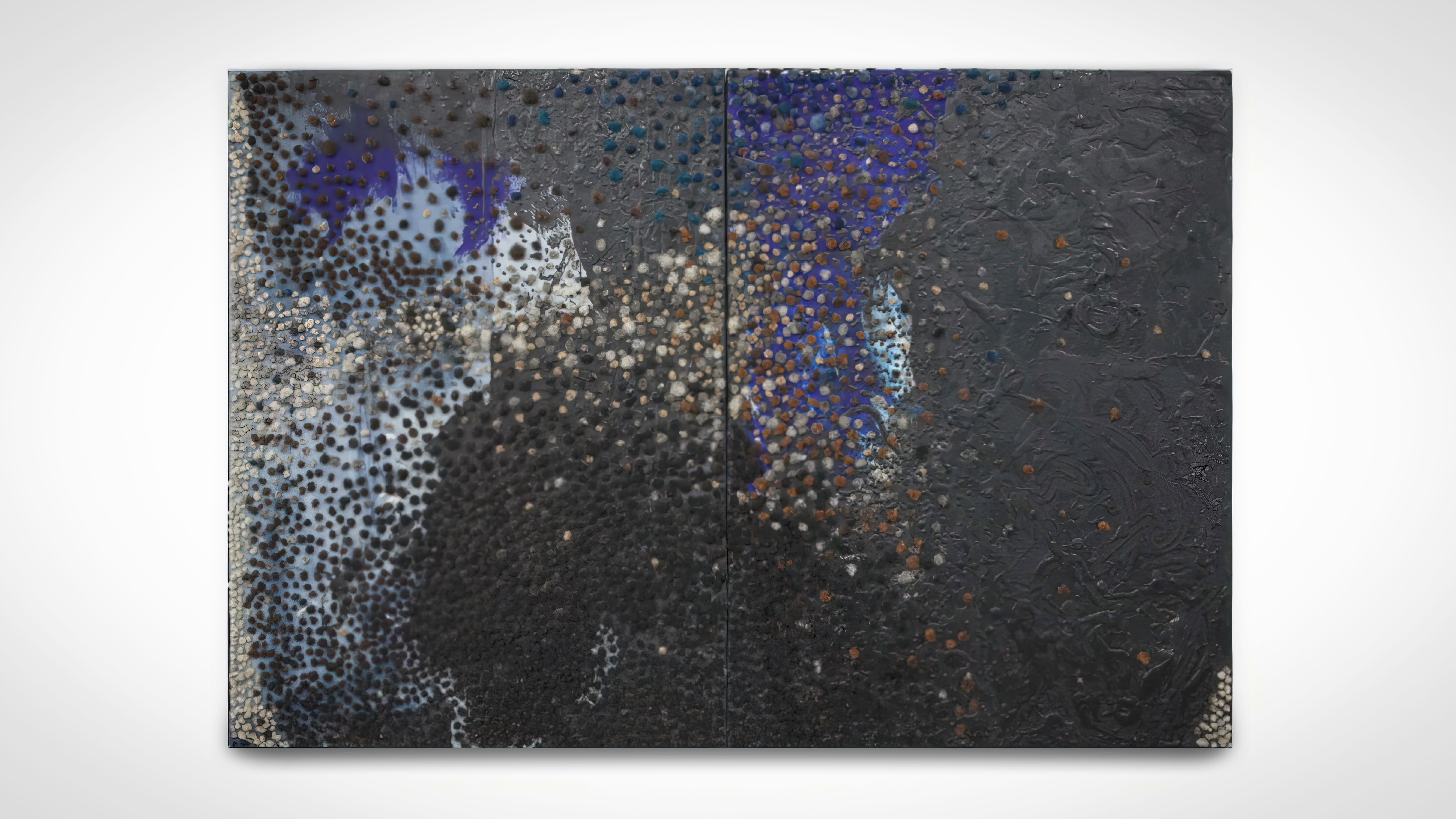

Adebunmi Gbadebo. I Sang the Blues (diptych), 2018-2019. Human hair locks, thread and paint on canvas, 48 × 75 in (121.9 × 190.5 cm). Image courtesy of the artist and Zeit Contemporary Art, New York

The use of nontraditional materials unites many of the artists included in this viewing room. What is your primary motivation behind using hair in your works?

I made the shift to work with Black hair as my primary medium during an art history class at the School of Visual Arts when my professor presented Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1865). The professor reflexively dismissed the “maid”– the other human and second largest form in the painting. He described the Black cat and the draped curtains in the image with more zest than the Black woman, Laure. This incident made me acutely aware that representation did not inherently provide Black life with more space for meaning. For me, Black hair became a way to center my people and our ancestry, history, and culture in my practice while literally using our bodies to do so. The process of working with hair has allowed me to utilize my community as an integral part of my studio practice. My material is our DNA. It’s my heritage. Hair donors turned gallery viewers connecting over a piece they are a part of is my resistance to the canon.

You have described your work as a double portrait and an abstracted history paper; could you elaborate on that and describe the role of memory and history on your art practice and its relation to abstraction?

In my series, History Paper, I turn human hair into paper and print archival images or documents on the surface. I often describe those pieces as a double portrait or abstracted history paper. In America, it wasn’t until 1870 when African descendents were recorded in the U.S federal census, creating what’s known in heritage studies as The 1870 Brick Wall. I was motivated by the erasure and complete destruction of these documents prior to this period to create a new archive where there's not only historical information or portraits being printed on the surface of the sheet, but the sheet itself is permeated with ancestral information that predates 1870. Abstraction allows me to acknowledge the histories that are embedded within my process and materials. The blue dye, the cotton, the Black hair, and the indigo, all carry the memory of the histories I depict in my work and through my process my body becomes a surrogate to that memory.

What are your thoughts on the legacy of Euro-American abstraction and how do you position your work in relation to it?

My thoughts on the legacy of Euro-American abstraction is: Where does their legacy begin? “Euro-American” abstraction is built from the shapes and forms of African symbols, masks, and sculptures. The fabrication of aesthetic and spiritual traditions. How do I position my work in relation to Euro-American, I don’t. When I chose Black hair as my material that was my way of decentering Euro-American art from my lexicon. I do recognize that I am a part of the long tradition of artists working in abstraction, and this includes Euro-American abstractionists. Especially having studied art in an institutional environment, I am intrinsically influenced by how European-Americans have pushed abstraction forward. But again, who influenced Euro-Americans, was it my legacy or theirs?