In contemporary art, few dialogues are as compelling as the unspoken exchange between American conceptual artist Sol LeWitt and Australian Aboriginal painter Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Their seemingly disparate artistic traditions converge in abstraction, demonstrating its universality while challenging conventional divisions between Western and Indigenous art.

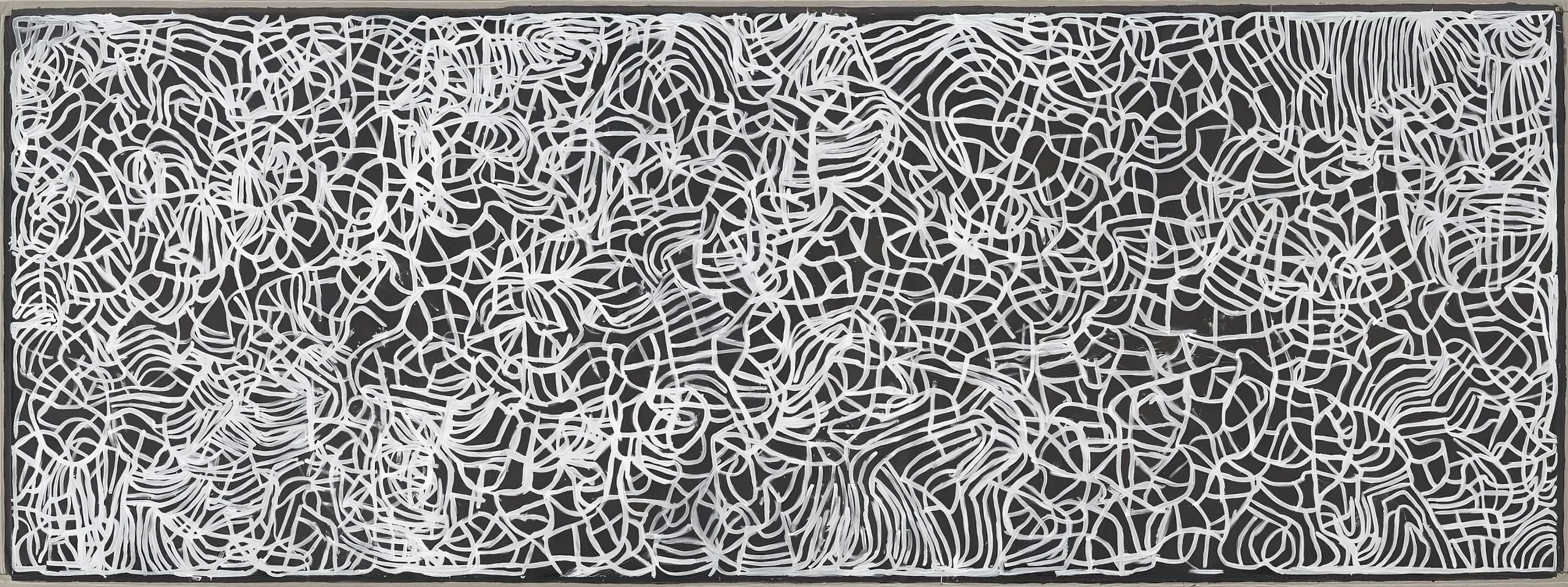

LeWitt, a pioneer of conceptual art, famously asserted that "the idea itself, even if not made visual, is as much a work of art as any finished product."[1] His methodical, geometric compositions emphasized concept over craft, often executed by others according to his precise instructions. Kngwarreye, by contrast, began painting in her late seventies after decades of working in batik and ceremonial sand painting, drawing on her Anmatyerre heritage. Her canvases, animated by rhythmic patterns and gestural marks, reflect an intimate connection to the land and the spiritual narratives of her people. While LeWitt sought to depersonalize authorship through systematic execution, Kngwarreye's abstraction was deeply personal, an extension of ancestral knowledge passed down through generations.

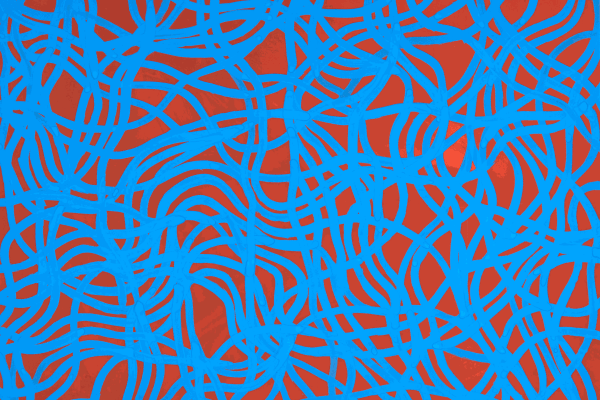

Their convergence can be traced back to the 1997 Venice Biennale, where LeWitt encountered Kngwarreye's work and expressed profound admiration, stating, "I feel a great affinity for [her] work and have learned a lot from her."[2] This revelation led him to collect over 30 works by Kngwarreye and other Central Desert artists between 1998 and 2005. Kngwarreye's dynamic surfaces, defined by pulsating dots and sweeping gestures, resonated with LeWitt's evolving aesthetic, particularly in his Loopy Doopy series, initiated in 1998. These wall drawings, composed of undulating bands of vibrant color, echo the fluid forms of Kngwarreye's paintings, revealing a transcultural dialogue that transcends geographic and historical divides.

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Anwerlarr anganenty (Big Yam Dreaming), 1995, synthetic polymer on canvas, 291.1 × 801.8 cm (114.6 × 315.6 in), Delmore Downs, NT. National Gallery of Victoria, gift of Donald & Janet Holt and family, 1995. © Emily Kam Kngwarray.

The 2022 exhibition Sol LeWitt: Affinities and Resonances at the Art Gallery of New South Wales further explored this connection. LeWitt's Wall Drawing #955: Loopy Doopy (red and purple) was displayed alongside works by Kngwarreye and Gloria Tamerre Petyarre, highlighting formal and conceptual resonances across their practices.[3] While LeWitt's abstraction is rooted in conceptualism and systematic execution, Kngwarreye's emerges from an intrinsic relationship to land and spirituality. Yet both artists employ repetition, pattern, and gestural energy to convey a sense of universality and timelessness.

From a postcolonial perspective, this artistic dialogue challenges traditional hierarchies that have historically marginalized Indigenous art forms. LeWitt's deep engagement with Aboriginal aesthetics represents a significant acknowledgment of their sophistication, disrupting the colonial tendency to relegate Indigenous works to ethnographic curiosity rather than recognizing them as integral to contemporary art. Moreover, his reliance on assistants to execute his designs mirrors the collective nature of many Indigenous art practices, where knowledge and techniques are transmitted through generations and artistic production is often communal rather than individualistic.

This cross-cultural exchange also prompts a reevaluation of the categories that define contemporary art. It destabilizes rigid distinctions between Western and non-Western traditions, underscoring abstraction as a universal language capable of bridging cultural divides. Curator Margo Neale observed that Kngwarreye's work "re-scaled the landscape with a cosmic dimension akin to a landscape of the Aboriginal mind, and this perspective is being written into the global imagination."[4] LeWitt's recognition of this sensibility-and its impact on his own evolving practice-signals an important shift in how modernist abstraction is understood beyond its Euro-American lineage.

The artistic interplay between Sol LeWitt and Emily Kame Kngwarreye exemplifies the power of abstraction to transcend cultural barriers. Despite their distinct origins, both artists distilled complex ideas into visual forms that communicate across time and place. Their mutual resonance challenges the boundaries of contemporary art, offering a testament to the interconnectedness of human expression.

___

1. Sol LeWitt, 'Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,' Artforum, June 1967.

2. Art Gallery of New South Wales, "Sol LeWitt: Affinities and Resonances," accessed March 2025, https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au.

3. Ibid.

4. Margo Neale, 'Emily Kame Kngwarreye and the Art of Australia's Indigenous Women,' The Art Story, accessed March 2025, https://www.theartstory.org/artist/kngwarreye-emily-kame/